- Home Page

- INL_WorldNewsSummary1

- INL_WorldNews_Summary2

- INL_News_Features1

- INL_Movie_News

- June_July07_News

- June_JulyA_07_News

- JUne_July0_NewsC

- BabyBlackSwanStudy

- MollyMeldrum_M_Gudinski

- Ellen_DeGeneres_TV_Show

- WorldVideoNews_Oct07

- WorldNews_June-July07D

- World_News_Nov_2007

- Bridget's_Daily_TV_Squad

- Mooly_Bloom_James_Joyce

- Guestbook

- YouTube_VideoClips1

- My_Space-The_Musical

- InternationalTheatreShow

- USA_Weekly_News_History1

- USA_Weekly_News_History2

- NewYork_What'sNew_Views

- NewYorkTimesSquare_WebCa

- SanFranciso-What's-On

- Freemasonry?_History

- Live_Leake_Great_Videos

- Rupert_Murdoch_MediaBarr

- AustNews_RealEstate

- Feature-Art_Work

- INLWorldNews_Dec08

- INLWorldNews_Jan09

- Canada_NPRNews

- EyeWitness_LocalNews

- USA_Video_News

- Business_News

- World_Video_News

- Entertainment_NewsP1

- Google's_Best_Videos

- End_Game_NewWorldOrder

- USA_2008_Elections

- CorruptPolice_Queensland

- WorldNewsHistory1

- Dublin_Fringe_Festival

- EdinburghFringe_Festival

- USAWeeklyNews_Awards

- Australian_Opera

- NewsHistory2008-P1

- WorldNewsHistory2008_P2

- WorldHistoryNews2008_P3

- WorldNewsHistory2008_P4

- WordlHistoryNews2008_P5

- Walter_Moreira_Salles

- RippOffClaims

- Phil_Spector_On_Trial

- BBC_Video_IPlayer_News

- DIANA_PRINCESSOFWALES

- USA_2008_ELECTIONS_P2

- WorldNews_Nov2008

- USA_News_November2008

- Obama_USA_President

- SCOTLAND'S_CRIMEGANGS

- MAG_Lloyds_HBOS_FIGHT

- LiverpoolFC_HicksGillett

- AustWeekendNews2001

- White_Gold_Cover_Up

- Iain_Gunn_Speaks_Out

- Liverpool_Football_Club

- Flickr_Christmas_Photos

- INL_SAUDI_ARABIA_NEWS

- BrokeBackMountain_Ledger

- Confucius_Quotations

- 72Point.com_Best_UKPR

- saddam_hussein_world

- INLNewsNewYear_2009

- BorisJohnson_LondonMayor

- Gaza_Israel_Hamas_War

- What Is_The_GazaStrip?

- World_Protests _Gaza

- Nov-December08News

- Photos_Israel _Gaza

- Gaza_Israel-ConflictNews

- INLNews_Jan_Feb_2009

- American_In_Gaza

- INLWorldNewsJan_Feb2

- BERRBusinessEnterpriseUK

- Gaza_Israel_Ceasefire

- USAWeeklyNews2007_08_P1

- Give Peace a Chance

- Yoko_Ono_Life Story

- John_Winston_Lennon

- Jonathan_Ross_BBC

- Russell_Brand

- Melbourne_2009BushFires

- INLNews_March09P2

- Dar_Williams_USAFolkRock

- INLNews_Hot_Topics

- INLMarch09News_P3

- INL_January09_News

- INLNewsJan_Feb2009_P2

- INL_MarchNews_P4

- INLNews_March09_P5

- INLNews_March09_P6

- INL News_March09_P7

- USA_IndependentMedia

- Bob_Dylan_Story

- NewYork'sEasterParade

- UnitedPeaceJusticeMarch

- Susan_Boyle_Singer

- INL_WorldNews_April09

- Naked_Ambition?

- Sabastian_Diaz_Director

- NightToRememberNewYork

- Lloyd_Carew-Reid_Justice

- FremantleMedia.com

- PippenDrysdale_FineArts

- INL's_Croatia_News

- Austin_Texas_News

- USA_Festival_Directory

- Diabetes_News

- MAY09_INLWorldNews

- MaliWomen'sPerformingArt

- INLNov08HistoryNews

- MichaelJacksonStory1

- MichaelJacksonMurdered?

- AmericanUnionMade?

- DeathofMichaelJackson2

- MichaelJacksonHistory3

- HottestWebNews

- TopMichaelJacksonNews1

- BloomergBusinessNews

- FansSuicideOverJackson

- MackennalEdgarBertram

- allmichaeljackson

- INLNewsMarch09P8

- INLNewsMarch09P9

- MichaelJacksonMurdered?2

- INLNewsMarch09P10

- RunningOfTheBulls

- MichaelJacksonVideoNews

- BBC_INLVideoNews

- AP_INLVideoNews

- Reuters_INLNewsVideo

- FOX _INLNewsVideo

- Fox_INLBusinessNews

- AFP_INL VideoNews

- Australia_INLNewsVideo

- CBC.ca_INLNewsVideo

- INLJuly09NewsP1

- INLNewsSept09

- BrookAstor_AnthonyAstor

- BNP_UK_NIckGriffin

- FindMadeleineMcCann.com

- WorldsMostPowerfulMen

- AdolfHitler_EvaBrownFilm

- MurdochToBuyBBCDebate

- MurdochSaysNoFreeNews

- MurdochToSueBBCForLosses

- ABCSlamsMurdochBBCAttack

- MurdochPapersOpenFireBBC

- GoogleMurdochDivorcing

- GoogleCorporateHistory

- MurdochBuyingUKElection

- MurdochBuyingUKElection

- UKWeeklyWorldNewsNov09

- INLWorldNewsDec2009

- INLWorldNewsNov2009

- BilderbergGroupHistory

- USAFreemasonPresidentsP1

- USA_PresidentsListP1

- USA_PresidentsListP2

- BilderbergGroupHistoryP2

- BilderbergGroupHistoryP3

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder2

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder4

- SurvivalOfElitePyramid

- CodexAlimentarius

- JFK_KennedyAssasination

- RothschildWorldControl1

- RothschildMurderHistory1

- WhoRothschildsMurdered2

- RothschildMoneyControl

- ObamaAntiChristIdentity

- RothschildsNewWorld2

- RothschildsNewWorld3

- RothschildsNewWorld4

- RothschildsNewWorld1

- RothschildsNewWorld2

- RothschildsNewWorld3

- RothschildsNewWorld4

- RothschildsNewWorld6

- WorldPressTVNewsJan2010

- RothschildsNewWorld5

- HitlerWasABritishAgent1

- WorldGovernmentAgenda1

- NWOPlanBankingCollapse1

- USA_Past-Present_Future1

- USA_Past-Present_Future1

- AdolfHitler_EvaBrownFilm

- WikiLeaksJulianAssange

- IlluminatiNewWolrdOrder1

- LeoZagami_RealIlluminati

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P2

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P3

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P4

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P4

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P6

- Leo_Zagami_Illuminati_P7

- Nebra_Astronomical_Clock

- INLNews_DailyWorldNews_1

- PeterMoonAussieCommedian

- AllanBond_DiBliss_WAust

- Marie-Claire_Bleasdale

- DidThurmonHaveFairTrial?

- RebekahBrooks_Arrested

- MadeleineMcCann_NewProbe

- VisionWatchReports_2012

- WorldVisionReportsJune12

- Scotlands-IndepenceFight

- HiddenHIstoryOfLondonP_1

- MicklebergStitchWestAust

- WhyWasNickClayMurderedP1

- WhyWasSeanHoareMurdered

- WhoMurderedThomasAllwood

- YahooMoviesEntertainment

- Rebekah_Brooks_Arrested1

- CIASellDrugs_MediaLiesP1

- HiddenHistoryOfLondonP_2

- MrX_InsideFileDisclosure

- MrWijatsFav_GooglePhotos

- Assange_FearsMurderInUSA

- CovertDepopulationTactic

- WeaponizedWeatherExposed

- JapaneseEarthquakeDebate

- GiseldaBlanco_Concaine

- LakeAnnecyFranceShooting

- CyberCrimeCyberCriminals

- RocketKIlledUSAmbassador

- USCoversUpPolishMassacre

- FaceBookIsWatchingYouNow

- DuchessofCambridge_Kate

- Mash_Before&AfterPhotos

- AntiDepressantsNightmare

- JimmySavileBBCdiedAged84

- JimmySavile_GuradianNews

- RothschildsMossadMI5_CIA

- WhoIsZbigniewBrzezinski

- BillClintons_BodyCountP1

- RothschildsSpyAgenciesP1

- BushHadPrior911Knowledge

- SirFrancisBoyle_Lawyer

- GlobalResearchWarOnDrugs

- NATO_OperationGladio

- RothschildMI5SovietAgent

- Ostrovsky_WayOfDeception

- CatarinaMiglioriniBrazil

- ToKnow_InfiniteAwareness

- GaryGlitter_PaulGlad_BBC

- ObamaVRomney_USA_Debate2

- INLNewsHistory3rdOct2012

- DailyWorldNews_INLNewsP1

- ObamaWins2012USAElection

- ChrisSpiveyWorldPutRight

- NimbinMardiGrassParade

- ChippingAwayTheBullSh_t

- TheSecretTeamLeroyProuty

- HowTheCIAIsRunSecretTeam

- PaulaBroadwell_DPetraeus

- MikeMorrell-CIADirector

- INLNewsCIAKGBSpyPhotosP1

- AssassinationBigBusiness

- MaxwellFrankClifford

- SandyHookSchoolShooting

- WhoRunsTheUK_MI5_orThePM

- SchapelleCorby_SetUp_Why

- CIA_MindControl_MKULTRA

- ProjectPaperClip_NaziCIA

- MI6_GlobalDrugTradeLords

- HitlersNaziPsychiatrists

- CIASellsDrugsMediaLies

- TriumphOfTruthBookStolen

- CIAMI6ControlDrugDealing

- MontgomeryClan_Scotland

- WorldHungerScandal

- UnfilteredINLWorldNewsP1

- MeetPrudenceMurdoch

- IceAgeArt_BritishMuseum

- FLOURIDEandDEMOCRACY

- DialMForMurdoch_Hacking

- ForbesRichList-2013

- Oxford-LegalAncecdotes

- LeadBellyBlues1888to1949

- ScotlandsFreePressAtRisk

- ScotlandNewPoliceInChaos

- FutureSpaceSettlementsP1

- MegaFloods-PastandFuture

- GeorgeCarlinFamousQuotes

- HitlerWasABritish

- EarthPastFutureGlenKealy

- MargaretThatcherIronLady

- Lady_MargaretThatcher

- MadMagazine-History

- FreemasonHistoryExposed1

- INL_EntertainmentNews_P1

- CorruptionHighCourtJudge

- Freemason-TheBrotherhood

- BehindSecretClosedDoors

- Jabobite-MasonControlWar

- Lord_PatrickStewartHodge

- MostDangerousMen_History

- WoolwichAttack-LeeRigby1

- MI5-behindWoolwichMurder

- Woolwich-RigbyTerrorNews

- WhoReallyRunsTheWorld?

- Murdoch_WendiDengDivorse

- EdwardSnowden_CIA-Prism

- HowCIACreatedBinLaden-GL

- MI6PrincessDiannaMurder1

- PrincessDiana-MI6Murder

- LadyGaGa-IlluminatiQueen

- Psychiatry_DeathIndustry

- MurderOfPrincessDianaP1

- CorruptPoliceInAustralia

- DroneTechnology_Effects1

- EffectsOfDroneTechnology

- CorruptPolice_BlueMurder

- IndianFunnyBlogsPictures

- IndianInterestingStories

- WikiLeaks-MIrrors-Cables

- Assange-AustralianSenate

- PrinceGeorge_UKRoyalBaby

- LadyDieFilm_DianaMurder1

- EdFringe.com2013EdFringe

- EdFringe.com_2013Fringe2

- EdFringe.comJustTheTonic

- EdFringe.comAssembly2013

- EdFringe.comUnderbelly13

- WomenWhoWank_FoolishPlay

- UKLandRegistryCorruption

- SyriaConflict_IsWarRight

- MafiaWars_INLNews

- JusticeForRaymondMcCord4

- BulgarianMafia-InControl

- LenWalterBuckeridge_BGC

- ChineseTriadsInAustralia

- LenBuckeridgeDiesAged_77

- MoneyLaundering-Ireland

- HitlersWarMachine-Farben

- RothchildsWorldControl3

- MarkZuckerberg_Zuckerman

- MarinaKeeganDied-22Years

- TheDarkAlliance-GaryWebb

- MoneyChangersHistoryP1

- TriumphOfTruth-TheBookP1

- TheGreatAmericanNovel_P1

- TheGreatAmericanNovel_P2

- TheGreatAmericanNovel_P3

- BlueMurder_CorruptPolice

- ValerieVisitsMateraItaly

- arcticbeacon.com-radioP1

- arcticbeacon.com-radioP2

- Australian_Drug_Busts_P1

- DrsDie_ForSavingChildren

- NewAgeGlobalistAgenda_P1

- Page 372

- BCCI_Criminal_Network

- HillaryClintonReport_P.1

- USElection_TrumpVHillary

- ClaremontSerialMurdersWA

- ClaremontSerialKillings2

- WestAustralianElections

- DrKarlO'Callaghan-Police

- MafiaAustraliaDrugMurder

- DonaldTrump_USAPresident

- Gus_McCann_Irish_Singer

- JimMorrisonRidersInStorm

- Jim_Morrison_TheDoors_P1

- Khashoggi_Slaying_ News

- WestAustralianCorruption

- Storm_DocumentariesP1

- celebritieswhomarriedfan

- MostExpensiveProperties

- Expensivehomesforsale_P1

- MovieStarsWhoHatedtoKiss

- Google_Bias_Investigated

- Glen_Kealy_The Sculptor1

- JulianAssange_Arrest_P.1

- JulianAssangeSnowdenFile

- globalelitetvdocumentary

- AnnieJacobsen_USA_Author

- PerthMintSwindleTheMovie

- TheGreatAmericanNovel4

Mr Wijat's friend Magic Rabbit

Mr Wijat's friend Magic Rabbit  http://www.easterlingentertainment.net

http://www.easterlingentertainment.netINLNews YahooMail HotMail GMail AOLMai

lUSA MAIL YahooMail HotMailGMail AOLMail MyWayMail CNNWorld IsraelVideoNs

INLNsNYTimes WashNs AustStockEx WorldMedia JapanNs AusNs World VideoNs WorldFinance ChinaDaily IndiaNs USADaily BBC EuroNsABCAust

WANs NZNews QldNs MelbAge AdelaideNs TasNews ABCTas DarwinNsUSA MA

Stories Video/Audio Reuters AP AFP The Christian Science Monitor U.S. News & World Report AFP Features Reuters Life! NPR The Advocate Pew Daily Number Today in History Obituaries Corrections Politics LocalNews BBC News

WhoIsZbigniewBrzezinski

http://inlnews.biz/BrezinskiTellsCFRControl.html

BrezinskiTellsCFRControl

Zbigniew Brzezinski - Easier to kill a million people than to control them.

//www.youtube.com/watch? v=lkOOBo45TZU&feature=player_ embedded#

Zbigniew Brzezinski - Easier to kill a million people than to control them.

//www.youtube.com/watch? v=lkOOBo45TZU&feature=player_ embedded#Zbigniew Brzezinski Obama's Top Foreign Policy Advisers, Professor of American Foreign PolicyStrategic Analysis and Foreign Policy National

Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, worked for Ronald Regan as Intelligence advisor, founder and trustee of the Trilateral Commission, a member of the Council For Foreign Relations (CFR) and Council for Strategic and International Studies, analysis, mastermind behind the creation of Ben Ladin and the terrorist Al Quieda organisation, international advisor for a number of major corporations, an associate of Henry Kissinger, co-chairman of the Bush Advisory Security Task Force in 1988 ...what a guy...

states the following belief, conviction and effective advice to Barrack Obama and to Barrach Oboma and

Zbigniew Brzezinski's employers and bosses...Jacob and Evilyn Rothchold and the rest Rothschild International Banking Family and their other evil and criminally insane International Baking Partners and Business associates and elite families

For the first time in human history ,.,.for the first time in all of human history.....almost all of mankind is politiclaly awake... andthese new and old major powers...face and yet another .... a novel reality...in some respect unprecidented ... and it is that while the lethality ..the lethality of their power is greater that ever.... their capacity to propose control ove rthe politicsally awakened masses of the world is at an all time low an unprecidented alll time low... I once put it rather pungently ... and I was flatered that the British Foreign Secretary repeated this...as follows ... namely in ealier times ...'.It was easier to control a million people literally...it was easiet to control a million people that physicly to kill a million people ... today it is infinitely easy to kill a million people than control a million people ..it is easier to kill that ot control...

Rupert says, " Now if you want to get really.... really ...really angry .... go buy this book.. it's called the Grand Chess Board .... American Primacy and it's Neo Stratigic Objectives... written by Zbigniew Brzezingski in 1997 ...I am going to read you some quotes from that book ...

| Zbigniew Brzezinski | |

|---|---|

|

|

| December 2010 photo |

10th United States National Security Advisor

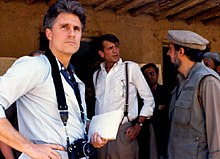

Spetsnaz troops interrogate a captured mujahideen with Western weapons in the background, 1986

Spetsnaz troops interrogate a captured mujahideen with Western weapons in the background, 1986 An Afghan mujahideen fighter demonstrates the use of a hand-held SA-7 surface-to-air missile

An Afghan mujahideen fighter demonstrates the use of a hand-held SA-7 surface-to-air missile

| In office January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 |

|

| President | Jimmy Carter |

|---|---|

| Deputy | David L. Aaron |

| Preceded by | Brent Scowcroft |

| Succeeded by | Richard V. Allen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski March 28, 1928 (age 84) Warsaw, Poland |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | McGill University Harvard University |

| Profession | Politician, critic |

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski (Polish: Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński, pronounced [ˈzbʲiɡɲɛf kaˈʑimʲɛʐ bʐɛˈʑiĩ̯skʲi]; born March 28, 1928) is a Polish American political scientist, geostrategist, and statesman who served as United States National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981.

Major foreign policy events during his term of office included the normalization of relations with the People's Republic of China (and the severing of ties with the Republic of China); the signing of the second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II); the brokering of the Camp David Accords; the transition of Iran from an important U.S. client state to an anti-Western Islamic Republic, encouraging dissidents in Eastern Europe and emphasizing human rights in order to undermine the influence of the Soviet Union;[1] the financing of the mujahideen in Afghanistan in response to the Soviet deployment of forces there[2] and the arming of these rebels to counter the Soviet invasion; and the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties relinquishing overt U.S. control of the Panama Canal after 1999.

Brzezinski is currently Robert E. Osgood Professor of American Foreign Policy at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies, a scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and a member of various boards and councils. He appears frequently as an expert on the PBS program The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, ABC News' This Week with Christiane Amanpour, and on MSNBC's Morning Joe, where his daughter, Mika Brzezinski, is co-anchor. In recent years, he has been a supporter of the Prague Process.[3]

| Iranian Revolution |

|

|

Articles

|

|

Soviet war in Afghanistan

The Soviet war in Afghanistan was a nine-year war during the Cold War fought by the Soviet Army and the Marxist-Leninist government of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan[20] against the Afghan Mujahideen guerrilla movement and foreign "Arab–Afghan" volunteers. The mujahideen received wide military and financial support from Pakistan,[21] also receiving direct and indirect support by the United States[2][3][4] and China.[22][23] The Afghan government fought with the intervention of the Soviet Union as its primary ally.[21]

The initial Soviet deployment of the 40th Army in Afghanistan began on December 24, 1979 under Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.[24] The final troop withdrawal started on May 15, 1988, and ended on February 15, 1989 under the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. Due to the interminable nature of the war, the conflict in Afghanistan has sometimes been referred to as the "Soviet Union's Vietnam War" or "the Bear Trap".[25][26][27]

|

||

Early years

Zbigniew Brzezinski was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1928. His family, members of the nobility (or "szlachta" in Polish), bore the Trąby coat of arms and hailed from Brzeżany in Galicia. This town is thought to be the source of the family name. Brzezinski's father was Tadeusz Brzeziński, a Polish diplomat who was posted to Germany from 1931 to 1935; Zbigniew Brzezinski thus spent some of his earliest years witnessing the rise of the Nazis. From 1936 to 1938, Tadeusz Brzeziński was posted to the Soviet Union during Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.[citation needed]

In 1938, Tadeusz Brzeziński was posted to Canada. In 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was agreed to by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union; subsequently the two powers invaded Poland. The 1945 Yalta Conference between the Allies allotted Poland to the Soviet sphere of influence, meaning Brzezinski's family could not safely return to their country.[citation needed] The Second World War had a profound effect on Brzezinski, who stated in an interview; "The extraordinary violence that was perpetrated against Poland did affect my perception of the world, and made me much more sensitive to the fact that a great deal of world politics is a fundamental struggle."[4]

Rising influence

After attending Loyola High School in Montreal – where he met Bora Karaman, one of his lifetime fellows and also mentors -[5] Brzezinski entered McGill University in 1945 to obtain both his Bachelor and Master of Arts degrees (received in 1949 and 1950 respectively). His Master's thesis focused on the various nationalities within the Soviet Union.[6] Brzezinski's plan for doing further studies in Great Britain in preparation for a diplomatic career in Canada fell through, principally because he was ruled ineligible for a scholarship he had won that was open to British subjects. Brzezinski then attended Harvard University to work on a doctorate, focusing on the Soviet Union and the relationship between the October Revolution, Vladimir Lenin's state, and the actions of Joseph Stalin. He received his doctorate in 1953; the same year, he traveled to Munich and met Jan Nowak-Jezioranski, head of the Polish desk of Radio Free Europe. He later collaborated with Carl J. Friedrich to develop the concept of totalitarianism as a way to more accurately and powerfully characterize and criticize the Soviets in 1956.

As a Harvard professor, he argued against Dwight Eisenhower's and John Foster Dulles's policy of rollback, saying that antagonism would push Eastern Europe further toward the Soviets. The Polish protests followed by Polish October and Hungarian Revolution in 1956 lent some support to Brzezinski's idea that the Eastern Europeans could gradually counter Soviet domination. In 1957, he visited Poland for the first time since he left as a child, and his visit reaffirmed his judgment that splits within the Eastern bloc were profound.

In 1958 he became a United States citizen. Despite his years of residence in Canada and the presence of family members there, he never became a Canadian citizen.

When in 1959 Brzezinski was not granted tenure at Harvard, he moved to New York City to teach at Columbia University.[7] Here he wrote Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict, which focused on Eastern Europe since the beginning of the Cold War. He also became a member of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York and attended meetings of the Bilderberg Group.

During the 1960 U.S. presidential elections, Brzezinski was an advisor to the John F. Kennedy campaign, urging a non-antagonistic policy toward Eastern European governments. Seeing the Soviet Union as having entered a period of stagnation, both economic and political, Brzezinski correctly predicted the future breakup of the Soviet Union along lines of nationality (expanding on his master's thesis).[6]

Brzezinski continued to argue for and support détente for the next few years, publishing "Peaceful Engagement in Eastern Europe" in Foreign Affairs,[8] and supporting non-antagonistic policies after the Cuban Missile Crisis, on the grounds that such policies might disabuse Eastern European nations of their fear of an aggressive Germany and pacify Western Europeans fearful of a superpower condominium along the lines of the Yalta Conference.[clarification needed]

In 1964, Brzezinski supported Lyndon Johnson's presidential campaign and the Great Society and civil rights policies, while on the other hand he saw Soviet leadership as having been purged of any creativity following the ousting of Khrushchev. Through Jan Nowak-Jezioranski, Brzezinski met with Adam Michnik, then a communist party member and future Polish Solidarity activist.

Brzezinski continued to support engagement with Eastern European governments, while warning against De Gaulle's vision of a "Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals." He also supported the Vietnam War. From 1966 to 1968, Brzezinski served as a member of the Policy Planning Council of the U.S. Department of State (President Johnson's October 7, 1966, "Bridge Building" speech was a product of Brzezinski's influence).

Events in Czechoslovakia further reinforced Brzezinski's criticisms of the right's aggressive stance toward Eastern European governments. His service to the Johnson administration, and his fact-finding trip to Vietnam, made him an enemy of the New Left, despite his advocacy of de-escalation of the United States' involvement in the war.

For the 1968 U.S. presidential campaign, Brzezinski was chairman of the Hubert Humphrey Foreign Policy Task Force. He advised Humphrey to break with several of President Johnson's policies, especially concerning Vietnam, the Middle East, and condominium with the Soviet Union.

Brzezinski called for a pan-European conference, an idea that would eventually find fruition in 1973 as the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe.[9] Meanwhile he became a leading critic of both the Nixon-Kissinger détente condominium, as well as McGovern's pacifism.[10]

In his 1970 piece Between Two Ages: America's Role in the Technetronic Era, Brzezinski argued that a coordinated policy among developed nations was necessary in order to counter global instability erupting from increasing economic inequality. Out of this thesis, Brzezinski co-founded the Trilateral Commission with David Rockefeller, serving as director from 1973 to 1976. The Trilateral Commission is a group of prominent political and business leaders and academics primarily from the United States, Western Europe and Japan. Its purpose was to strengthen relations among the three most industrially advanced regions of the capitalist world. Brzezinski selected Georgia governor Jimmy Carter as a member.

Government

Jimmy Carter announced his candidacy for the 1976 presidential campaign to a skeptical media and proclaimed himself an "eager student" of Brzezinski.[citation needed] Brzezinski became Carter's principal foreign policy advisor by late 1975. He became an outspoken critic of the Nixon-Kissinger over-reliance on détente, a situation preferred by the Soviet Union, favoring the Helsinki process instead, which focused on human rights, international law and peaceful engagement in Eastern Europe. Brzezinski has been considered to be the Democrats' response to Republican Henry Kissinger.[11] Carter engaged Ford in foreign policy debates by contrasting the Trilateral vision with Ford's détente.[12]

After his victory in 1976, Carter made Brzezinski National Security Advisor. Earlier that year, major labor riots broke out in Poland, laying the foundations for Solidarity. Brzezinski began by emphasizing the "Basket III" human rights in the Helsinki Final Act, which inspired Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia shortly thereafter.[13]

Brzezinski had a hand in writing parts of Carter's inaugural address, and this served his purpose of sending a positive message to Soviet dissidents.[14] The Soviet Union and Western European leaders both complained that this kind of rhetoric ran against the "code of détente" that Nixon and Kissinger had established.[15][16] Brzezinski ran up against members of his own Democratic Party who disagreed with this interpretation of détente, including Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. Vance argued for less emphasis on human rights in order to gain Soviet agreement to Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), whereas Brzezinski favored doing both at the same time. Brzezinski then ordered Radio Free Europe transmitters to increase the power and area of their broadcasts, a provocative reversal of Nixon-Kissinger policies.[17] West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt objected to Brzezinski's agenda, even calling for the removal of Radio Free Europe from German soil.[18]

The State Department was alarmed by Brzezinski's support for East German dissidents and objected to his suggestion that Carter's first overseas visit be to Poland. He visited Warsaw, met with Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski (against the objection of the U.S. Ambassador to Poland), recognizing the Roman Catholic Church as the legitimate opposition to communist rule in Poland.[19]

By 1978, Brzezinski and Vance were more and more at odds over the direction of Carter's foreign policy. Vance sought to continue the style of détente engineered by Nixon-Kissinger, with a focus on arms control. Brzezinski believed that détente emboldened the Soviets in Angola and the Middle East, and so he argued for increased military strength and an emphasis on human rights. Vance, the State Department, and the media criticized Brzezinski publicly as seeking to revive the Cold War.

Brzezinski advised Carter in 1978 to engage the People's Republic of China and traveled to Beijing to lay the groundwork for the normalization of relations between the two countries. This also resulted in the severing of ties with the United States' longtime anti-Communist ally the Republic of China. Also in 1978, Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyła was elected Pope John Paul II – an event which the Soviets believed[citation needed] Brzezinski orchestrated. President Carter told reporters that the new Pope was a friend of Dr. Brzezinski.1979 saw two major strategically important events: the overthrow of U.S. ally the Shah of Iran, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The Iranian Revolution precipitated the Iran hostage crisis, which would last for the rest of Carter's presidency. Brzezinski anticipated the Soviet invasion, and, with the support of Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the People's Republic of China, he created a strategy to undermine the Soviet presence. See below under "Major Policies – Afghanistan."

Using this atmosphere of insecurity, Brzezinski led the United States toward a new arms buildup and the development of the Rapid Deployment Forces – policies that are both more generally associated with Ronald Reagan now. In 1980, Brzezinski planned[citation needed] Operation Eagle Claw, which was meant to free the hostages in Iran using the newly created Delta Force and other Special Forces units. The mission was a failure and led to Secretary Vance's resignation.

Brzezinski was criticized widely in the press and became the least popular member of Carter's administration.[citation needed] Edward Kennedy challenged President Carter for the 1980 Democratic nomination, and at the convention, Kennedy's delegates loudly booed Brzezinski.[citation needed] Hurt by internal divisions within his party and a stagnant domestic economy, Carter lost the 1980 presidential election in a landslide.

Brzezinski, acting under a lame duck Carter presidency, but encouraged that Solidarity in Poland had vindicated his style of engagement with Eastern Europe, took a hard-line stance against what seemed like an imminent Soviet invasion of Poland. He even made a midnight phone call to Pope John Paul II – whose visit to Poland in 1979 had foreshadowed the emergence of Solidarity – warning him in advance. The U.S. stance was a significant change from previous reactions to Soviet repression in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

In 1981 President Carter presented Brzezinski with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After power

Brzezinski left office concerned about the internal division within the Democratic party, arguing that the dovish McGovernite wing would send the Democrats into permanent minority.

He had mixed relations with the Reagan administration. On the one hand, he supported it as an alternative to the Democrats' pacifism[clarification needed],[citation needed] but he also criticized it as seeing foreign policy in overly black-and-white terms.

He remained involved in Polish affairs, critical of the imposition of martial law in Poland in 1981, and more so of Western European acquiescence to its imposition in the name of stability. Brzezinski briefed U.S. vice-president George H. W. Bush before his 1987 trip to Poland that aided in the revival of the Solidarity movement.

In 1985, under the Reagan administration, Brzezinski served as a member of the President's Chemical Warfare Commission. From 1987 to 1988, he worked on the U.S. National Security Council–Defense Department Commission on Integrated Long-Term Strategy. From 1987 to 1989 he also served on the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board.

In 1988, Brzezinski was co-chairman of the Bush National Security Advisory Task Force and endorsed Bush for president, breaking with the Democratic party. Brzezinski published The Grand Failure the same year, predicting the failure of Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms and the collapse of the Soviet Union in a few more decades. He said there were five possibilities for the Soviet Union: successful pluralization, protracted crisis, renewed stagnation, coup (by the KGB or Soviet military), or the explicit collapse of the Communist regime. He called collapse "at this stage a much more remote possibility" than protracted crisis. He also predicted that the chance of some form of communism existing in the Soviet Union in 2017 was a little more than 50% and that when the end did come it would be "most likely turbulent". In the event, the Soviet system collapsed totally in 1991 following Moscow's crackdown on Lithuania's attempt to declare independence, the Nagorno-Karabakh War of the late 1980s, and scattered bloodshed in other republics. This was a less violent outcome than Brzezinski and other observers anticipated.

In 1989 the Communists failed to mobilize support in Poland, and Solidarity swept the general elections. Later the same year, Brzezinski toured Russia and visited a memorial to the Katyn Massacre. This served as an opportunity for him to ask the Soviet government to acknowledge the truth about the event, for which he received a standing ovation in the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Ten days later, the Berlin Wall fell, and Soviet-supported governments in Eastern Europe began to totter.

Strobe Talbott, one of Brzezinski's long-time critics, conducted an interview with him for TIME magazine entitled Vindication of a Hardliner.

In 1990 Brzezinski warned against post–Cold War euphoria. He publicly opposed the Gulf War,[citation needed] arguing that the United States would squander the international goodwill it had accumulated by defeating the Soviet Union and that it could trigger wide resentment throughout the Arab world. He expanded upon these views in his 1992 work Out of Control.

However, Brzezinski was prominently critical of the Clinton administration's hesitation to intervene against the Serb forces in the Bosnian war.[20] He also began to speak out against Russia's First Chechen War, forming the American Committee for Peace in Chechnya. Wary of a move toward the reinvigoration of Russian power, Brzezinski negatively viewed the succession of former KGB agent Vladimir Putin after Boris Yeltsin. In this vein, he became one of the foremost advocates of NATO expansion. He later came out in support of the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia during the Kosovo war.[21]

Present Day

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, Brzezinski was criticized for his role in the formation of the Afghan mujaheddin network. He countered that blame ought to be laid at the feet of the Soviet Union's invasion, which radicalized the relatively stable Muslim society.

Brzezinski was a leading critic of the George W. Bush administration's "war on terror". In 2004, Brzezinski wrote The Choice, which expanded upon The Grand Chessboard but sharply criticized George W. Bush's foreign policy. He defended the book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy and was an outspoken critic of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[22]

In August 2007, Brzezinski endorsed Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama. He stated that Obama "recognizes that the challenge is a new face, a new sense of direction, a new definition of America's role in the world."[23] – also saying, "What makes Obama attractive to me is that he understands that we live in a very different world where we have to relate to a variety of cultures and people."[24] In September 2007 during a speech on the Iraq war, Obama introduced Brzezinski as "one of our most outstanding thinkers," but some pro-Israel commentators questioned his criticism of the Israel lobby in the United States.[22] In a September 2009 interview with The Daily Beast, Brzezinski replied to a question about how aggressive President Obama should be in insisting Israel not conduct an air strike on Iran, saying: "We are not exactly impotent little babies. They have to fly over our airspace in Iraq. Are we just going to sit there and watch?"[25] This was interpreted by some supporters of Israel as supporting the downing of Israeli jets by the United States in order to prevent an attack on Iran.[26][27] In 2011, Brzezinski supported the NATO intervention against the forces of Muammar Gaddafi in the Libyan civil war, calling non-intervention "morally dubious" and "politically questionable".[28]

Personal life

Brzezinski is married to Czech-American sculptor Emilie Benes (grand-niece of the second Czechoslovak president, Edvard Beneš), with whom he has three children. His son, Mark Brzezinski (b. 1965), a lawyer who served on President Clinton's National Security Council as an expert on Russia and Southeastern Europe and who was a partner in McGuire Woods LLP, serves as the US ambassador to Sweden. His daughter, Mika Brzezinski (b. 1967), is a television news presenter and co-host of MSNBC's weekday morning program, Morning Joe, where she provides regular commentary and reads the news headlines for the program. His son Ian served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Europe and NATO and was a principal at Booz Allen Hamilton. Ian Brzezinski is a Senior Fellow in the International Security Program and is on the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Advisors Group. Key highlights of his tenure as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Europe and NATO Policy (2001–2005) include the expansion of NATO membership in 2004, the consolidation and reconfiguration of the Alliance’s command structure, the standing up of the NATO Response Force and the coordination of European military contributions to U.S.- and NATO-led operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and the Balkans.[29]

As Carter's National Security Advisor

President Carter chose Zbigniew Brzezinski for the position of National Security Adviser (NSA) because he wanted an assertive intellectual at his side to provide him with day-to-day advice and guidance on foreign policy decisions. Brzezinski would preside over a reorganized National Security Council (NSC) structure, fashioned to ensure that the NSA would be only one of many players in the foreign policy process.

Brzezinski's task was complicated by his (hawkish) focus on East-West relations in an administration where many cared a great deal about North-South relations and human rights.

Initially, Carter reduced the NSC staff by one-half and decreased the number of standing NSC committees from eight to two. All issues referred to the NSC were reviewed by one of the two new committees, either the Policy Review Committee (PRC) or the Special Coordinating Committee (SCC). The PRC focused on specific issues, and its chairmanship rotated. The SCC was always chaired by Brzezinski, a circumstance he had to negotiate with Carter to achieve. Carter believed that by making the NSA chairman of only one of the two committees, he would prevent the NSC from being the overwhelming influence on foreign policy decisions it had been under Kissinger's chairmanship during the Nixon administration. The SCC was charged with considering issues that cut across several departments, including oversight of intelligence activities, arms control evaluation, and crisis management. Much of the SCC's time during the Carter years was spent on SALT issues.

The Council held few formal meetings, convening only 10 times, compared with 125 meetings during the 8 years of the Nixon and Ford administrations. Instead, Carter used frequent, informal meetings as a decision-making device, typically his Friday breakfasts, usually attended by the Vice President, the secretaries of State and Defense, Brzezinski, and the chief domestic adviser. No agendas were prepared and no formal records were kept of these meetings, sometimes resulting in differing interpretations of the decisions actually agreed upon. Brzezinski was careful, in managing his own weekly luncheons with secretaries Vance and Brown in preparation for NSC discussions, to maintain a complete set of notes. Brzezinski also sent weekly reports to the President on major foreign policy undertakings and problems, with recommendations for courses of action. President Carter enjoyed these reports and frequently annotated them with his own views. Brzezinski and the NSC used these Presidential notes (159 of them) as the basis for NSC actions.

From the beginning, Brzezinski made sure that the new NSC institutional relationships would assure him a major voice in the shaping of foreign policy. While he knew that Carter would not want him to be another Kissinger, Brzezinski also felt confident that the President did not want Secretary of State Vance to become another Dulles and would want his own input on key foreign policy decisions.

Brzezinski's power gradually expanded into the operational area during the Carter Presidency. He increasingly assumed the role of a Presidential emissary. In 1978, for example, Brzezinski traveled to Beijing to lay the groundwork for normalizing U.S.–PRC relations. Like Kissinger before him, Brzezinski maintained his own personal relationship with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin. Brzezinski had NSC staffers monitor State Department cable traffic through the Situation Room and call back to the State Department if the President preferred to revise or take issue with outgoing State Department instructions. He also appointed his own press spokesman, and his frequent press briefings and appearances on television interview shows made him a prominent public figure, although perhaps not nearly as much as Kissinger had been under Nixon.

The Soviet military invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 significantly damaged the already tenuous relationship between Vance and Brzezinski. Vance felt that Brzezinski's linkage of SALT to other Soviet activities and the MX, together with the growing domestic criticisms in the United States of the SALT II Accord, convinced Brezhnev to decide on military intervention in Afghanistan. Brzezinski, however, later recounted that he advanced proposals to maintain Afghanistan's independence but was frustrated by the Department of State's opposition. An NSC working group on Afghanistan wrote several reports on the deteriorating situation in 1979, but President Carter ignored them until the Soviet intervention destroyed his illusions. Only then did he decide to abandon SALT II ratification and pursue the anti-Soviet policies that Brzezinski proposed.

The Iranian revolution was the last straw for the disintegrating relationship between Vance and Brzezinski. As the upheaval developed, the two advanced fundamentally different positions. Brzezinski wanted to control the revolution and increasingly suggested military action to prevent Ayatollah Khomeini from coming to power, while Vance wanted to come to terms with the new Islamic Republic of Iran. As a consequence, Carter failed to develop a coherent approach to the Iranian situation. In the growing crisis atmosphere of 1979 and 1980 due to the Iranian hostage situation, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and a deepening economic crisis, Brzezinski's anti-Soviet views gained influence but could not end the Carter administration's malaise. Vance's resignation following the unsuccessful mission to rescue the American hostages in March 1980, undertaken over his objections, was the final result of the deep disagreement between Brzezinski and Vance.

Major policies

During the 1960s Brzezinski articulated the strategy of peaceful engagement for undermining the Soviet bloc and while serving on the State Department Policy Planning Council, persuaded President Johnson to adopt in October 1966 peaceful engagement as U.S. strategy, placing détente ahead of German reunification and thus reversing prior U.S. priorities.

During the 1970s and 1980s, at the height of his political involvement, Brzezinski participated in the formation of the Trilateral Commission in order to more closely cement U.S.–Japanese–European relations. As the three most economically advanced sectors of the world, the people of the three regions could be brought together in cooperation that would give them a more cohesive stance against the communist world.

While serving in the White House, Brzezinski emphasized the centrality of human rights as a means of placing the Soviet Union on the ideological defensive. With Jimmy Carter in Camp David, he assisted in the attainment of the Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty. He actively supported Polish Solidarity and the Afghan resistance to Soviet invasion, and provided covert support for national independence movements in the Soviet Union. He played a leading role in normalizing U.S.–PRC relations and in the development of joint strategic cooperation, cultivating a relationship with Deng Xiaoping, for which he is thought very highly of in mainland China to this day.

In the 1990s he formulated the strategic case for buttressing the independent statehood of Ukraine, partially as a means to ending a resurgence of the Russian Empire, and to drive Russia toward integration with the West, promoting instead "geopolitical pluralism" in the space of the former Soviet Union. He developed "a plan for Europe" urging the expansion of NATO, making the case for the expansion of NATO to the Baltic states. He also served as William Clinton's emissary to Azerbaijan in order to promote the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline. Subsequently, he became a member of Honorary Council of Advisors of U.S.-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce (USACC). Further, he led, together with Lane Kirkland, the effort to increase the endowment for the U.S.-sponsored Polish-American Freedom Foundation from the proposed $112 million to an eventual total of well over $200 million.

He has consistently urged a U.S. leadership role in the world, based on established alliances, and warned against unilateralist policies that would destroy U.S. global credibility and precipitate U.S. global isolation.

Afghanistan

A 2002 article by Michael Rubin stated that in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, the United States sought rapprochement with the Afghan government—a prospect that the USSR found unacceptable due to the weakening Soviet leverage over the regime. Thus, the Soviets intervened to preserve their influence in the country.[30] According to Vance's close aide Marshall Shulman "the State Department worked hard to dissuade the Soviets from invading."[31] In February 1979, U.S. Ambassador Adolph "Spike" Dubs was murdered in Kabul after Afghan security forces burst in on his kidnappers. The U.S. then reduced bilateral assistance and terminated a small military training program. All remaining assistance agreements were ended after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Following the Soviet invasion, the United States supported diplomatic efforts to achieve a Soviet withdrawal. In addition, generous U.S. contributions to the refugee program in Pakistan played a major part in efforts to assist Afghan refugees.

Brzezinski, known for his hardline policies on the Soviet Union, initiated in 1979 a campaign supporting mujaheddin in Pakistan and Afghanistan, which was run by Pakistani security services with financial support from the Central Intelligence Agency and Britain's MI6.[32] This policy had the explicit aim of promoting radical Islamist and anti-Communist forces. Bob Gates, in his book Out Of The Shadows, wrote that Pakistan had been pressuring the United States for arms to aid the rebels for months, but that the Carter administration refused in the hope of finding a diplomatic solution to avoid war.[33] Brzezinski seems to have been in favor of the provision of arms to the rebels, while Vance's State Department, seeking a peaceful settlement, publicly accused Brzezinski of seeking to "revive" the Cold War. Brzezinski has stated that the United States provided communications equipment and limited financial aid to the mujahideen prior to the "formal" invasion, but only in response to the Soviet deployment of forces to Afghanistan and the 1978 coup, and with the intention of preventing further Soviet encroachment in the region.[34]

Years later, in a 1997 CNN/National Security Archive interview, Brzezinski detailed the strategy taken by the Carter administration against the Soviets in 1979:

We immediately launched a twofold process when we heard that the Soviets had entered Afghanistan. The first involved direct reactions and sanctions focused on the Soviet Union, and both the State Department and the National Security Council prepared long lists of sanctions to be adopted, of steps to be taken to increase the international costs to the Soviet Union of their actions. And the second course of action led to my going to Pakistan a month or so after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, for the purpose of coordinating with the Pakistanis a joint response, the purpose of which would be to make the Soviets bleed for as much and as long as is possible; and we engaged in that effort in a collaborative sense with the Saudis, the Egyptians, the British, the Chinese, and we started providing weapons to the Mujaheddin, from various sources again – for example, some Soviet arms from the Egyptians and the Chinese. We even got Soviet arms from the Czechoslovak communist government, since it was obviously susceptible to material incentives; and at some point we started buying arms for the Mujaheddin from the Soviet army in Afghanistan, because that army was increasingly corrupt.[35]

Milt Bearden wrote in The Main Enemy that Brzezinski, in 1980, secured an agreement from King Khalid of Saudi Arabia to match U.S. contributions to the Afghan effort dollar for dollar and that Bill Casey would keep that agreement going through the Reagan administration.[36]

The Soviet invasion and occupation resulted in the deaths of as many as 2 million Afghans.[37] In 2010, Brzezinski defended the arming of the rebels in response, saying that it "was quite important in hastening the end of the conflict," thereby saving the lives of thousands of Afghans, but "not in deciding the conflict, because....even though we helped the mujaheddin, they would have continued fighting without our help, because they were also getting a lot of money from the Persian Gulf and the Arab states, and they weren't going to quit. They didn't decide to fight because we urged them to. They're fighters, and they prefer to be independent. They just happen to have a curious complex: they don't like foreigners with guns in their country. And they were going to fight the Soviets. Giving them weapons was a very important forward step in defeating the Soviets, and that's all to the good as far as I'm concerned." When he was asked if he thought it was the right decision in retrospect (given the Taliban's subsequent rise to power), he said: "Which decision? For the Soviets to go in? The decision was the Soviets', and they went in. The Afghans would have resisted anyway, and they were resisting. I just told you: in my view, the Afghans would have prevailed in the end anyway, 'cause they had access to money, they had access to weapons, and they had the will to fight."[38] Likewise; Charlie Wilson said: "The U.S. had nothing whatsoever to do with these people's decision to fight ... but we'll be damned by history if we let them fight with stones."[39]

The supplying of billions of dollars in arms to the Afghan mujahideen militants was one of the CIA's longest and most expensive covert operations.[40] The CIA provided assistance to the insurgents through the Pakistani secret services, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), in a program called Operation Cyclone. At least 3 billion in U.S. dollars were funneled into the country to train and equip troops with weapons. Together with similar programs by Saudi Arabia, Britain's MI6 and SAS, Egypt, Iran, and the People's Republic of China,[41] the arms included Stinger missiles, shoulder-fired, antiaircraft weapons that they used against Soviet helicopters. Pakistan's secret service, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), was used as an intermediary for most of these activities to disguise the sources of support for the resistance.

No Americans trained or had direct contact with the mujahideen.[42] The skittish CIA had fewer than 10 operatives in the region because it "feared it would be blamed, like in Guatemala."[43] Civilian personnel from the U.S. Department of State and the CIA frequently visited the Afghanistan-Pakistan border area during this time.

With U.S. and other funding, the ISI armed and trained over 100,000 insurgents. On July 20, 1987, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country was announced pursuant to the negotiations that led to the Geneva Accords of 1988,[44] with the last Soviets leaving on February 15, 1989.

The early foundations of al-Qaida were allegedly built in part on relationships and weaponry that came from the billions of dollars in U.S. support for the Afghan mujahideen during the war to expel Soviet forces from that country.[45] However, scholars such as Jason Burke, Steve Coll, Peter Bergen, Christopher Andrew, and Vasily Mitrokhin have argued that Bin Laden was "outside of CIA eyesight" and that there is "no support" in any "reliable source" for "the claim that the CIA funded bin Laden or any of the other Arab volunteers who came to support the mujahideen."[46][47][48][49]

Iran

Facing a revolution, the Shah of Iran sought help from the United States. Iran occupied a strategic place in U.S. policy in the Middle East, acting as an important ally and a buffer against Soviet influence in the region. The U.S. ambassador to Iran, William H. Sullivan, recalls that Brzezinski "repeatedly assured Pahlavi that the U.S. backed him fully."[citation needed] These reassurances would not, however, amount to substantive action on the part of the United States. On November 4, 1978, Brzezinski called the Shah to tell him that the United States would "back him to the hilt."[citation needed] At the same time, certain high-level officials in the State Department decided that the Shah had to go, regardless of who replaced him.[citation needed] Brzezinski and U.S. Secretary of Energy James Schlesinger (formerly Secretary of Defense under Gerald Ford) continued to advocate that the U.S. support the Shah militarily. Even in the final days of the revolution, when the Shah was considered doomed no matter what the outcome of the revolution, Brzezinski still advocated a U.S. invasion to keep Iran under U.S. influence.[citation needed] President Carter could not decide how to appropriately use force and opposed another U.S.-backed coup d'état. He ordered the aircraft carrier Constellation to the Indian Ocean but ultimately allowed a regime change. A deal was worked out with the Iranian generals to shift support to a moderate government,[citation needed] but this plan fell apart when Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers swept the country, taking power on February 12, 1979.

China

Shortly after taking office in 1977, President Carter again reaffirmed the United States' position of upholding the Shanghai Communique. The United States and People's Republic of China announced on December 15, 1978, that the two governments would establish diplomatic relations on January 1, 1979. This required that the United States sever relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan. Consolidating U.S. gains in befriending communist China was a major priority stressed by Brzezinski during his time as National Security Advisor.

The most important strategic aspect of the new U.S.–Chinese relationship was in its effect on the Cold War. China was no longer considered part of a larger Sino-Soviet bloc but instead a third pole of power due to the Sino-Soviet Split, helping the United States against the Soviet Union.

In the Joint Communique on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations dated January 1, 1979, the United States transferred diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The United States reiterated the Shanghai Communique's acknowledgment of the PRC position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is a part of China; Beijing acknowledged that the United States would continue to carry on commercial, cultural, and other unofficial contacts with Taiwan. The Taiwan Relations Act made the necessary changes in U.S. domestic law to permit unofficial relations with Taiwan to continue.

In addition the severing relations with the Republic of China, the Carter administration also agreed to unilaterally pull out of the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, withdraw U.S. military personnel from Taiwan, and gradually reduce arms sales to the Republic of China. There was widespread opposition in the U.S. Congress, notably from Republicans, due to the Republic of China's status as an anti-Communist ally in the Cold War. In Goldwater v. Carter, Barry Goldwater made a failed attempt to stop Carter from terminating the mutual defense treaty.

PRC Vice-premier Deng Xiaoping's January 1979 visit to Washington, D.C., initiated a series of high-level exchanges, which continued until the Tiananmen Square massacre, when they were briefly interrupted. This resulted in many bilateral agreements, especially in the fields of scientific, technological, and cultural interchange and trade relations. Since early 1979, the United States and the PRC have initiated hundreds of joint research projects and cooperative programs under the Agreement on Cooperation in Science and Technology, the largest bilateral program.

On March 1, 1979, the United States and People's Republic of China formally established embassies in Beijing and Washington. During 1979, outstanding private claims were resolved, and a bilateral trade agreement was concluded. U.S. vice-president Walter Mondale reciprocated vice-premier Deng's visit with an August 1979 trip to China. This visit led to agreements in September 1980 on maritime affairs, civil aviation links, and textile matters, as well as a bilateral consular convention.

As a consequence of high-level and working-level contacts initiated in 1980, U.S. dialogue with China broadened to cover a wide range of issues, including global and regional strategic problems, political-military questions – including arms control, UN and other multilateral organization affairs, and international narcotics matters.

Arab-Israeli conflict

On October 10, 2007, Brzezinski along with other influential signatories sent a letter to President George W. Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice titled 'Failure Risks Devastating Consequences'. The letter was partly an advice and a warning of the failure of an upcoming[50] U.S.-sponsored Middle East conference scheduled for November 2007 between representatives of Israelis and Palestinians. The letter also suggested to engage in "a genuine dialogue with Hamas" rather than to isolate it further.[51]

A Chilling Proposal by Barack Obama

The shocking comment Barack Obama does not want you to hear!

Audacity Hope Media Fox Jeremiah Wright Democrat Republican Vote 2008 Controversy Controversial Church Pastor Commentary Political Commercial Politics Analysis Grassroots Gotcha! Outreach News Change Primary Primaries Pennsylvania Guam Indiana North Carolina West Virginia Kentucky Oregon Puerto Rico Montana South Dakota Convention DNC November Guns Faith Bitter Cling

Zbigniew Brzezinski - Easier to kill a million people than to control them.

Zbigniew Brzezinski - Easier to kill a million people than to control them.

//www.youtube.com/watch?Zbigniew

Brzezinski Obama's Top Foreign Policy Advisers, Professor of American

Foreign PolicyStrategic Analysis and Foreign Policy National

Security

Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, worked for Ronald Regan as

Intelligence advisor, founder and trustee of the Trilateral Commission, a

member of the Council For Foreign Relations (CFR) and Council for

Strategic and International Studies, analysis, mastermind behind the

creation of Ben Ladin and the terrorist Al Quieda organisation,

international advisor for a number of major corporations, an associate

of Henry Kissinger, co-chairman of the Bush Advisory Security Task Force

in 1988 ...what a guy...

states the following belief, conviction and effective advice to Barrack Obama and to Barrach Oboma and

Zbigniew Brzezinski's employers and bosses...Jacob and Evilyn Rothchold and the rest Rothschild International Banking Family and their other evil and criminally insane International Baking Partners and Business associates and elite families

For the first time in human history ,.,.for the first time in all of human history.....almost all of mankind is politiclaly awake... andthese new and old major powers...face and yet another .... a novel reality...in some respect unprecidented ... and it is that while the lethality ..the lethality of their power is greater that ever.... their capacity to propose control ove rthe politicsally awakened masses of the world is at an all time low an unprecidented alll time low... I once put it rather pungently ... and I was flatered that the British Foreign Secretary repeated this...as follows ... namely in ealier times ...'.It was easier to control a million people literally...it was easiet to control a million people that physicly to kill a million people ... today it is infinitely easy to kill a million people than control a million people ..it is easier to kill that ot control...

Rupert says, " Now if you want to get really.... really ...really angry .... go buy this book.. it's called the Grand Chess Board .... American Primacy and it's Neo Stratigic Objectives... written by Zbigniew Brzezingski in 1997 ...I am going to read you some quotes from that book ...

Zbigniew Brzezinski

The Grand Chessboard

American Primacy And It's Geostrategic Imperatives

Key Quotes From Zbigniew Brzezinksi's Seminal 1998 Book

Note: For highly revealing news articles on elite groups and secret societies in which Zbigniew Brzezinski is involved, click here.

"Ever since the continents started interacting politically,

some five hundred years ago, Eurasia has been the center of world

power."- (p. xiii)

"It is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges capable of dominating Eurasia and thus of also challenging America. The formulation of a comprehensive and integrated Eurasian geostrategy is therefore the purpose of this book." (p. xiv)

"How America 'manages' Eurasia is critical. A power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world's three most advanced and economically productive regions. A mere glance at the map also suggests that control over Eurasia would almost automatically entail Africa's subordination, rendering the Western Hemisphere and Oceania geopolitically peripheral to the world's central continent. About 75 per cent of the world's people live in Eurasia, and most of the world's physical wealth is there as well, both in its enterprises and underneath its soil. Eurasia accounts for about three-fourths of the world's known energy resources." (p.31)

"Never before has a populist democracy attained international supremacy. But the pursuit of power is not a goal that commands popular passion, except in conditions of a sudden threat or challenge to the public's sense of domestic well-being. The economic self-denial (that is, defense spending) and the human sacrifice (casualties, even among professional soldiers) required in the effort are uncongenial to democratic instincts. Democracy is inimical to imperial mobilization." (p.35)

"The momentum of Asia's economic development is already generating massive pressures for the exploration and exploitation of new sources of energy and the Central Asian region and the Caspian Sea basin are known to contain reserves of natural gas and oil that dwarf those of Kuwait, the Gulf of Mexico, or the North Sea." (p.125)

"In the long run, global politics are bound to become increasingly uncongenial to the concentration of hegemonic power in the hands of a single state. Hence, America is not only the first, as well as the only, truly global superpower, but it is also likely to be the very last." (p.209)

"Moreover, as America becomes an increasingly multi-cultural society, it may find it more difficult to fashion a consensus on foreign policy issues, except in the circumstance of a truly massive and widely perceived direct external threat." (p. 211)

Zbigniew Brzezinski's Background

According

to his resume, Zbigniew Brzezinski lists the following achievements:

Harvard Ph.D. in 1953

Counselor, Center for Strategic

and International Studies

Professor of American Foreign

Policy, Johns Hopkins University

National Security Advisor

to President Jimmy Carter (1977-81)

Trustee and founder of the Trilateral

Commission

International advisor of several

major US/Global corporations

Associate of Henry Kissinger

Under Ronald Reagan - member

of NSC-Defense Department Commission on Integrated Long-Term Strategy

Under Ronald Reagan - member

of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board

Past member, Board of Directors,

The Council on Foreign Relations

1988 - Co-chairman of the Bush

National Security Advisory Task Force.

Zbigniew Brzezinski is also a past attendee and presenter at conferences of the Bilderberg Group - a non-partisan affiliation of the wealthiest, most powerful families and corporations on the planet.

The Grand Chessboard by Zbigniew Brzezinski – More Quotes

"The last decade of the twentieth century has witnessed a tectonic shift in world affairs. For the first time ever, a non-Eurasian power has emerged not only as a key arbiter of Eurasian power relations but also as the world's paramount power. The defeat and collapse of the Soviet Union was the final step in the rapid ascendance of a Western Hemisphere power, the United States, as the sole and, indeed, the first truly global power." (p. xiii)

"The attitude of the American public toward the external projection of American power has been much more ambivalent. The public supported America's engagement in World War II largely because of the shock effect of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor." (pp 24-5)

"For America, the chief geopolitical prize is Eurasia... Now a non-Eurasian power is preeminent in Eurasia - and America's global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained." (p.30)

"America's withdrawal from the world or because of the sudden emergence of a successful rival - would produce massive international instability. It would prompt global anarchy." (p. 30)

"Two basic steps are thus required: first, to identify the geostrategically dynamic Eurasian states that have the power to cause a potentially important shift in the international distribution of power and to decipher the central external goals of their respective political elites and the likely consequences of their seeking to attain them;... second, to formulate specific U.S. policies to offset, co-opt, and/or control the above..." (p. 40)

"To put it in a terminology that harkens back to the more brutal age of ancient empires, the three grand imperatives of imperial geostrategy are to prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and to keep the barbarians from coming together." (p.40)

"Henceforth, the United States may have to determine how to cope with regional coalitions that seek to push America out of Eurasia, thereby threatening America's status as a global power." (p.55)

"Uzbekistan, nationally the most vital and the most populous of the central Asian states, represents the major obstacle to any renewed Russian control over the region. Its independence is critical to the survival of the other Central Asian states, and it is the least vulnerable to Russian pressures." (p. 121)

[Referring to an area he calls the "Eurasian Balkans" and a 1997 map in which he has circled the exact location of the current conflict - describing it as the central region of pending conflict for world dominance] "Moreover, they [the Central Asian Republics] are of importance from the standpoint of security and historical ambitions to at least three of their most immediate and more powerful neighbors, namely Russia, Turkey and Iran, with China also signaling an increasing political interest in the region. But the Eurasian Balkans are infinitely more important as a potential economic prize: an enormous concentration of natural gas and oil reserves is located in the region, in addition to important minerals, including gold." (p.124)

"The world's energy consumption is bound to vastly increase over the next two or three decades. Estimates by the U.S. Department of energy anticipate that world demand will rise by more than 50 percent between 1993 and 2015, with the most significant increase in consumption occurring in the Far East. The momentum of Asia's economic development is already generating massive pressures for the exploration and exploitation of new sources of energy and the Central Asian region and the Caspian Sea basin are known to contain reserves of natural gas and oil that dwarf those of Kuwait, the Gulf of Mexico, or the North Sea." (p.125)

"Uzbekistan is, in fact, the prime candidate for regional leadership in Central Asia." (p.130)

"Once pipelines to the area have been developed, Turkmenistan's truly vast natural gas reserves augur a prosperous future for the country's people." (p.132)

"In fact, an Islamic revival - already abetted from the outside not only by Iran but also by Saudi Arabia - is likely to become the mobilizing impulse for the increasingly pervasive new nationalisms, determined to oppose any reintegration under Russian - and hence infidel - control." (p. 133).

"For Pakistan, the primary interest is to gain Geostrategic depth through political influence in Afghanistan - and to deny to Iran the exercise of such influence in Afghanistan and Tajikistan - and to benefit eventually from any pipeline construction linking Central Asia with the Arabian Sea." (p.139)

"Turkmenistan... has been actively exploring the construction of a new pipeline through Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Arabian Sea..." (p.145)

"It follows that America's primary interest is to help ensure that no single power comes to control this geopolitical space and that the global community has unhindered financial and economic access to it." (p148)

"China's growing economic presence in the region and its political stake in the area's independence are also congruent with America's interests." (p.149)

"America is now the only global superpower, and Eurasia is the globe's central arena. Hence, what happens to the distribution of power on the Eurasian continent will be of decisive importance to America's global primacy and to America's historical legacy." (p.194)

"Without sustained and directed American involvement, before long the forces of global disorder could come to dominate the world scene. And the possibility of such a fragmentation is inherent in the geopolitical tensions not only of today's Eurasia but of the world more generally." (p.194)

"With warning signs on the horizon across Europe and Asia, any successful American policy must focus on Eurasia as a whole and be guided by a Geostrategic design." (p.197)

"That puts a premium on maneuver and manipulation in order to prevent the emergence of a hostile coalition that could eventually seek to challenge America's primacy." (p. 198)

"The most immediate task is to make certain that no state or combination of states gains the capacity to expel the United States from Eurasia or even to diminish significantly its decisive arbitration role." (p. 198)

"Moreover, as America becomes an increasingly multi-cultural society, it may find it more difficult to fashion a consensus on foreign policy issues, except in the circumstance of a truly massive and widely perceived direct external threat." (p. 211)

Note: This essay is drawn largely from the work of former LAPD narcotics investigator Michael Ruppert in his essay "A War in the Planning for Four Years: How Stupic Do They Think We Are?"

To order The Grand Chessboard by Zbigniew Brzezinski through amazon.com, click here

For revealing news articles on elite groups in which Brzezinski is involved, click here

To explore our reliable, verifiable two-page summary of the 9/11 cover-up, click

here

To visit our reliable, verifiable ten-page summary of the 9/11 cover-up,

click here

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Brzezinski on Iran

Massive unemployment could lead to riots says Dr. Brzezinski

Michael Ruppert confronts CIA director about Drug Laundering

Former CIA Official Exposes Bush Administration Fraud

http://representativepress.

The Bush Administration has committed fraud before. See background information on the fraud committed by the Bush Administration to get us into the Iraq War:

The Problem Was Not "Faulty Intelligence," the Problem Was Dishonestly Selecting And Omitting Intelligence

http://representativepress.

Senate Hearing on Iraq Pre-War Intelligence

http://representativepress.

US Intelligence About Iraq Didn't Really Fail, It Was Manipulated

http://representativepress.

Beyond all reasonable doubt, the Bush Administration is guilty of the high crime of lying our nation into war.

http://representativepress.

Read Dealing with Tehran by Flynt Leverett here:http://www.newamerica.

See video: Elliott Abrams is another NeoCon that doesn't respect the Constitution

//www.youtube.com/watch?

Good Morning America learns that Bin Laden is CIA

Ruppert about Brzezinski (2001) : part 1 of 2

//www.youtube.com/watch?

Ruppert about Brzezinski (2001) : part 2 of 2

Ruppert about Brzezinski (2001) : part 2 of 2

Why I know Barack Obama is a phony

//www.youtube.com/watch?If you are so inclined, please upload your own german-accented Brzezinski quote and post it as a video response. Here is the infamous Brzezinski quote: "Moreover, as America becomes an increasingly multicultural society, it may find it more difficult to fashion a concensus on foreign policy issues, except in the circumstances of a truly massive and widely perceived direct external threat."

Ruppert about Brzezinski (2001) : part 1 of 2

//www.youtube.com/watch?

Ruppert about Brzezinski (2001) : part 2 of 2

//www.youtube.com/watch?

Zbigniew Brzezinski gets a tough question from 911 truther

//www.youtube.com/watch?

I DID NOT SHOOT THIS VIDEO, Please give all the props to Luke Rudkowski at WeAreChange NYC. Please get in touch with him @ wearechange.org

With only hours notice, CHANGE discovered that NWO Globalist Zbigniew Brzezinski was giving a speech at the YMCA in Manhattan. Luke was able to get in and ask some questions about his recent statements regarding false-flag terror attacks being staged by the Bush Administration, and his funding of the Taliban during the Afghan war with the Soviets. He was then directly confronted on the CFR's involvement in planning the attacks of 911.

WEARECHANGE.ORG

Iranian Revolution

| Iranian Revolution (Islamic Revolution, 1979 Revolution) انقلاب اسلامی |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Protesters in Tehran, 1979 |

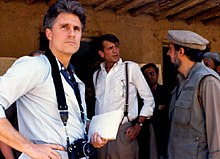

The Shah of Iran (left) meeting with members of the U.S. government: Alfred Atherton, William Sullivan, Cyrus Vance, Jimmy Carter, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, 197

The Shah of Iran (left) meeting with members of the U.S. government: Alfred Atherton, William Sullivan, Cyrus Vance, Jimmy Carter, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, 197Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution (also known as the Islamic Revolution or 1979 Revolution;[3][4][5][6][7][8] Persian: انقلاب اسلامی, Enghelābe Eslāmi orانقلاب بیست و دو بهمن) refers to events involving the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and its replacement with an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution.

Demonstrations against the Shah commenced in October 1977, developing into a campaign of civil resistance that was partly secular and partly religious,[9] and intensified in January 1978.[10] Between August and December 1978 strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country. The Shah left Iran for exile on January 16, 1979 as the last Persian monarch and in the resulting power vacuum two weeks later Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to a greeting by several million Iranians.[11][12] The royal reign collapsed shortly after on February 11 when guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting.[13][14] Iran voted by national referendum to become an Islamic Republic on April 1, 1979,[15] and to approve a new democratic-theocratic hybrid constitution whereby Khomeini became Supreme Leader of the country, in December 1979.

The revolution was unusual for the surprise it created throughout the world:[16] it lacked many of the customary causes of revolution (defeat at war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military),[17] produced profound change at great speed,[18] was massively popular,[19] and replaced a westernising monarchy with a theocracy based on Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists (or velayat-e faqih). Its outcome—an Islamic Republic "under the guidance of an extraordinary religious scholar from Qom"—was, as one scholar put it, "clearly an occurrence that had to be explained" .

Causes

Iran was an overly centralized royal power structure state, which was heavily protected by a lavishly financed army and security services.[21][22][23] The revolution was in part a conservative backlash against the Westernizing and secularizing efforts of the Western-backed Shah,[24] and a liberal backlash to social injustice and other shortcomings of the ancien régime.[25]